A BELFAST historian has set out to challenge the “Anglo-centric” narrative of the Nine Years War in Ireland by giving a comprehensive reassessment of the military dimensions of the conflict.

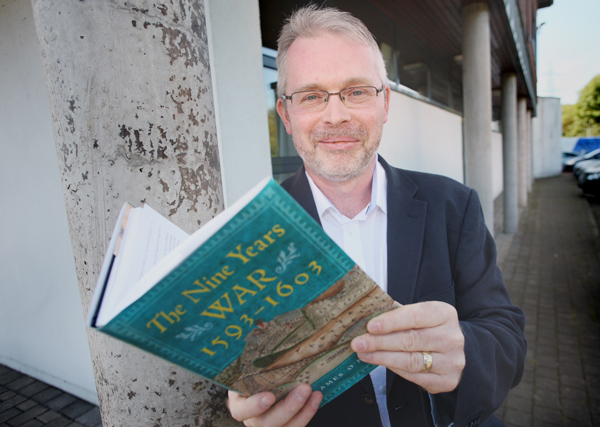

In his new book, The Nine Years War, Dr James O’Neill has given what is arguably the most complete modern assessment of what would become the final years of Gaelic Ireland.

In 1593 the Irish and their Spanish allies, led by Hugh O’Neill, the Gaelic Earl of Tyrone, waged war to end English rule. Some modern histories have referenced the war, setting out an all too brief timeline of events including the momentous Irish victory at the Yellow Ford in Armagh, and notably, their ultimate defeat at Kinsale in 1601, where they were crushed at the hand of Lord Mountjoy and his forces.

The defeat saw the last of the Gaelic lords flee Ireland in what would become known as the Flight of the Earls, paving the way for the plantation of Ulster.

According to Dr O’Neill, the typical narrative of the war suggests that the “primitive Irish” military was doomed to failure, and the plantation was a “modernising trend”. However, he insists that his research has revealed the contrary.

“An august academic told me once before – I’ll not mention any names – that this research had been done before, that we already know all of this, but luckily I ignored him,” he said.

“There’s not a single narrative of the Nine Years War, which is quite shocking. There are books that deal with bits of it, books with a few chapters, but you can’t get a book on it.

“The military revolution had fundamentally changed the way that war was fought. A lot of what we have seen is a very Anglo-centric or unionist narrative of the war, which said that the Irish were primitive, or that it was inevitable that they would get beat because of course, they were Irish – they were backward. That follows on with the plantations, which were seen as a way to ‘civilize’ the Irish.

“That’s just one side of the story, but what about the nationalist perspective? The Irish didn’t want to be seen as these modernising Gaels either. The annals back then, all the way up to the Celtic revival movement, depicted pure Irishness as this image of warriors like Cú Chulainn, spears and swords and paint on their faces. But what really happened didn’t fit with that narrative. The reality was that the Irish were far more dependent on firepower. Eighty per cent of O’Neill’s men had guns compared to around 50 per cent of the English.

“O’Neill very much lived in an Anglo-Irish world and a native Irish world. At worst people would say that he copied what the English military were doing, but what he actually did was take the strengths of what they were doing, like replacing swords with guns, and grafted that onto the strengths of Irish warfare, which was all about speed and mobility. Whenever he did that he transformed warfare in a way that hadn’t been seen before.

He continued: “He also created a network of alliances and not just in Ulster. The fighting was focused in Ulster, but that was a misdirection that fooled the English during the war, but also fooled later historians into thinking that his efforts were concentrated there.

“He made the English fight in Armagh so that he could expand his control and alliances outside of Ulster. By the time it came to the Battle of the Yellow Ford, which was the biggest Irish defeat of English arms ever, O’Neill had already spread to Tipperary, which caused the collapse of the Munster plantation.”

The Gaelic Irish were also influenced by their Spanish allies, which Dr O’Neill said helped them train a modern army fully capable of defeating the English in the field.

“There was a lot of Spanish influence of the way they fired their weapons, the way they moved over ground, but they didn’t just copy it, they very much adapted it. When the English first came up against them they didn’t know how to deal with them.

“The English had been fighting the Spanish for years, so they knew how to fight them, but when O’Neill turned up with this hybrid, they couldn’t understand it. Time and time again the English were flatfooted and slow, but the Irish were quick and adaptable. They also had a level of co-operation that had them totally stunned until Mountjoy came along.

“Mountjoy was one of the first to realise that he wasn’t fighting against the Irish of old, and he created a broad front strategy.

“He used the English naval strength, which O’Neill had nothing to compare to. He fundamentally reorganised English troops and training, and in some ways copied the Irish; he saw their speed over ground and their operational ability to move across country.

“He also saw the weakness in Irish loyalties, because of all the different families. The way the Irish succession system worked through the Tánaiste meant that someone always lost out. Mountjoy started to support the people who lost out in dynastic disputes to undermine certain loyalties.

“The real killer, for strategic purposes, was that he saw the Midlands and all the supplies were coming out of the north to O’Neill’s southern allies. He focused on the Midlands and cut off those supplies. Also, whenever their gunpowder supply was cut off they had to depend on untrained pike men. The reality was that the Irish were far more dependent on modern weaponry and firepower.”

As well as highlighting the military advances of the Gaelic Irish, Dr O’Neill’s book uncovers the truly modern economic and industrial advances during a war that was paid for with “gold and not cowhides”.

Reflecting on his contribution to the historiography of the period he said: “This period was the last of Gaelic Ulster before the plantation, and plantation narrative is that it is a modernising trend compared to the old archaic ways. What I want this book to show is that the native Gaels were modernising at a rate far quicker than the English. On the ground, the level of and openness to change was far higher than even I knew when I began my research.

“It should change people’s idea of what Gaelic Ulster and Gaelic Ireland was like. Mostly it’s all about introducing the modernising Gael. Ireland was not some colonial backwater, and this wasn’t just a colonial war because of the parallels with European warfare.”

The Nine Years War 1593-1603 by Dr James O’Neill can be purchased on Amazon, priced £28.35p.