Last week, Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond announced his intention for the country to face a referendum in 2014 in which the Scottish people would choose whether to remain part of the UK or become fully independent.

The issue has long been debated but has emerged as a pressing matter since Salmond’s Scottish National Party took a majority in the Scottish parliamentary elections last May.

Last Wednesday (January 25), Salmond announced the question posed on the ballot paper would be ‘Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?’ saying the question was “short, straightforward and clear”.

Away from the glare of Scotland, some have asked what independence would mean for Northern Ireland, its place in the UK and unionists who have made it their lives to maintain that link.

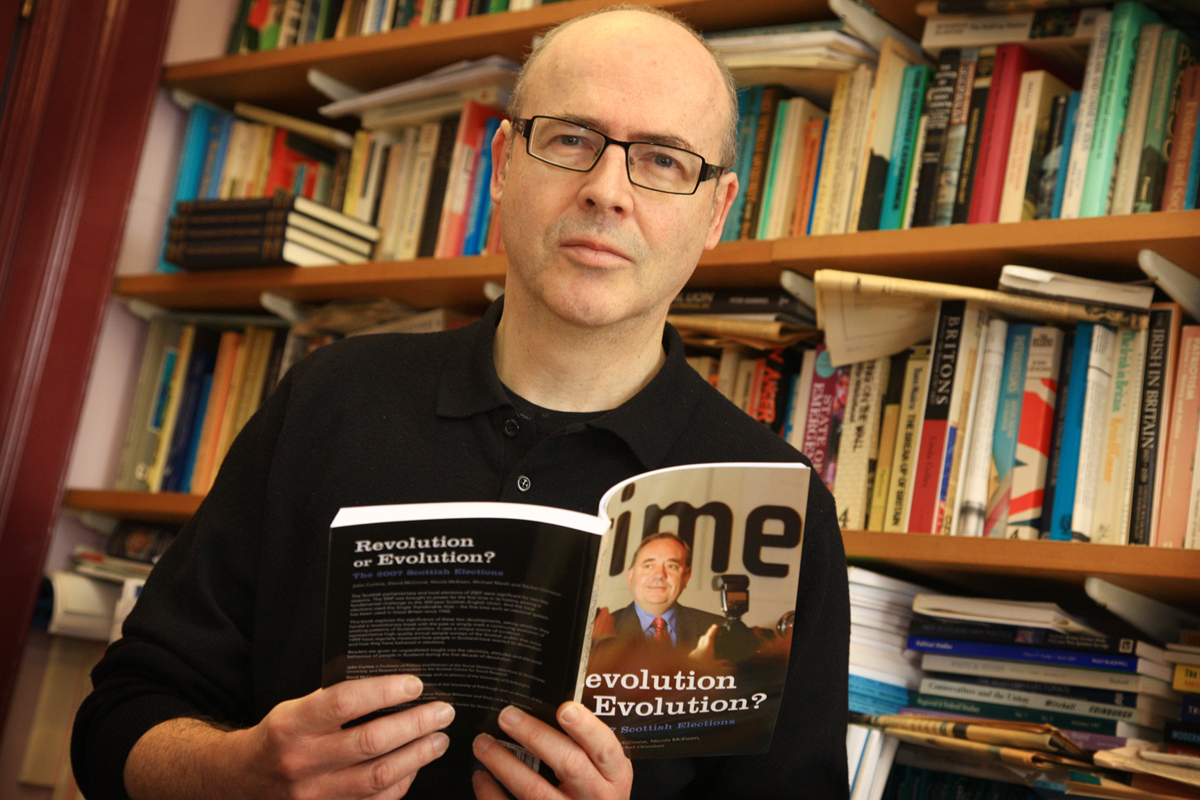

Professor Graham Walker of Queen’s University’s Irish Politics Centre is an expert in the contemporary politics of both Scotland and the north, with a special focus on unionism.

A Scotsman himself, Prof Walker said there is still a debate over whether the motion to make Scotland independent would gain the requisite amount of backing to pass in the current political climate.

“Salmond’s intention all along was to hold the referendum in the second half of the parliament but the Westminster government thought there was an advantage to them in trying to bring it forward. That meant he was able to depict them as interfering and they had to back down on that issue.

“The result really depends on a number of factors. But if the questions remains as a simple yes or no then my belief is it would be a narrow victory for no. I base that on current evidence which suggests independence has the backing of only around a third of the electorate.

“However, that gap is going to narrow because I don’t think there will be any economic improvement in the UK as a whole by then and Salmond is quite persuasive in the view of presenting a new independent Scotland as having a vibrant economy.

“He can play the card of having oil reserves and although there are a lot of imponderables when it comes to economics, what he is effectively asking is do people want to carry on in a UK that is toiling economically or do they want to take the chance and have a new start to build growth? I think he can paint quite an attractive picture around that.”

Prof Walker said if, hypothetically speaking, the independence motion passed, if could have serious ramifications here.

“The first thing is it won’t happen immediately. There would be all sorts of negotiations about Scotland’s share of the national debt and the assets of the state, not to mention the debate over defence, those debates will be long and torturous.

“But assuming the vote is decisively in favour, what is left is a very odd entity – the United Kingdom of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. That is going to pose a lot of soul searching for people here in particular. It’s the outcome unionists most dread because they have invested a lot in recent years in a relationship with Scotland.

“It’s been quite central to their notion, so Scotland leaving the union leaves them adrift. The cultural links would still be there but being part of the same political structure is very important to unionists.

“I think they would have a feeling that they are somewhat isolated because within unionism there is a long-standing perception the central government in London does not understand them and that would be intensified in that case. You could see the unionist position being a lot shakier in a truncated UK because England could then see the UK enterprise isn’t worth maintaining and Northern Ireland isn’t worth maintaining.”

However, Prof Walker said he didn’t believe that situation would “kill off” unionism as a political belief.

“Looking at it economically, I don’t see the Republic being in any position to be attractive to unionists. Of course because of pragmatic politics you will get a few takers for a united Ireland because of the continuing economic downturn.

“But the Republic would have to take on the welfare spending that Westminster currently reluctantly provides and that would not happen. So I don’t see an end to the union and therefore I don’t see an end to unionism.

“But it would lead to an identity crisis for unionists because so much of their self-image is built around close relationship with the rest of the UK, especially Scotland.”

There has been talk suggesting a successful yes vote would lead to a growth of support for a referendum concerning the future of this state.

“It is possible that that would happen but you would have to have the people who think there is a point to it and who would lobby for constitutional change for a united Ireland or indeed an independent Northern Ireland. I just don’t see the groundswell at this moment for either.

“There is a pragmatic acceptance that a united Ireland is still someway off if it is ever going to happen, whereas an independent Northern Ireland fills people with the jitters for all sorts of reasons – the economic viability and also that it could reopen a lot of political instability.

“There is also a possibility that people here might start to go down the road Scotland has been on for the last few years in terms of getting greater powers. That would require devolution here to be a bit more purposeful but if the parties can show agreement on tackling difficult issues like the 11 Plus, the growing confidence from that will result in demands for greater powers and there could be further developments there.”

“Nothing will remain the same after this referendum and although I predict it will not result in independence, I do think it is going to lead to a lot of hard thinking about the shape the UK should take.”

No matter the outcome of the referendum, Prof Walker says there will be changes to the political structures we currently operate under.

“Nothing will remain the same after this referendum and although I predict it will not result in independence, I do think it is going to lead to a lot of hard thinking about the shape the UK should take.

“That could be in terms of a federal direction and maybe feed into other issues that have been on the agenda for some time such as reform of the House of Lords. We could have parts of the UK having autonomy to a certain point and the upper house in Westminster being where everyone is represented, while the House of Commons is a purely English parliament.

“As the Scottish question intensifies in the next two or three years, more people will think about these issues more widely and connect them up, saying we have to think hard about how we run this quite complex entity.”