IN the early eighties, the formulation of the weekly Andersonstown News editorial followed a strict procedure.

Séamus Mac Seáin, polymath and printer who wrote no other material for the people’s press would call the staff, such as it was, into the editorial room — formerly the living room of a flat above shops on the Andersonstown Road.

The Bóthar Seoighe founder would then read his editorial aloud from three or four pages of A4 typewriter paper where he had penned in biro in his unique hurried cursive script his thought for the day. The rest of us would nod or suggest amendments as he blazed through another scorching leader column. Once agreed, deletions marked out with pen and additions scrawled in, the editorial would be handed over to the undauntable Anne Girvan to be typed up for that evening’s edition.

The opinion pieces were red-hot and righteous, speaking for a readership which found itself unrecognisable in the mainstream news reports — as with so many peoples who found themselves on the wrong side of British ‘peacemaking’. Indeed, those once-colonized peoples all merited an editorial shout-out whether it be famine in India, torture in Aden, calumny in Cyprus or concentration camps in Kenya.

Kenya and its first president, the former prisoner Jomo Kenyatta, occupied a special place of infamy in the British press when Séamus was growing up in fifties St James’ — ensuring the ‘Mau Mau’ who led that country’s freedom struggle a pedestal of pride of equal measure in the Andersonstown News.

All of which brings us to the ties that bind Kenya’s most revered writer Ngugi wa Thiongo to the nationalist people of Belfast.

For Ngugi was the first internationally-recognised Kenyan figure to repudiate the pejorative nickname Mau Mau, born from settler slang, and insist that the Kenyan rebels be called by the true name of their movement, The Kenya Land and Freedom Army.

For this and for demanding the fruits of their struggle go to those who carried the heaviest load during eight hard years of warfare from 1952-1960, Ngugi was ostracised by the government of Jomo Kenyatta and eventually found himself detained without trial under legislation first introduced by the British.

His brilliant oeuvre includes some of the greatest African novels of the 20th Century as well as his seminal work on cultural colonisation, Decolonising the Mind. Latterly and now based in California, Ngugi has insisted in writing all his work in his native Gikuyu.

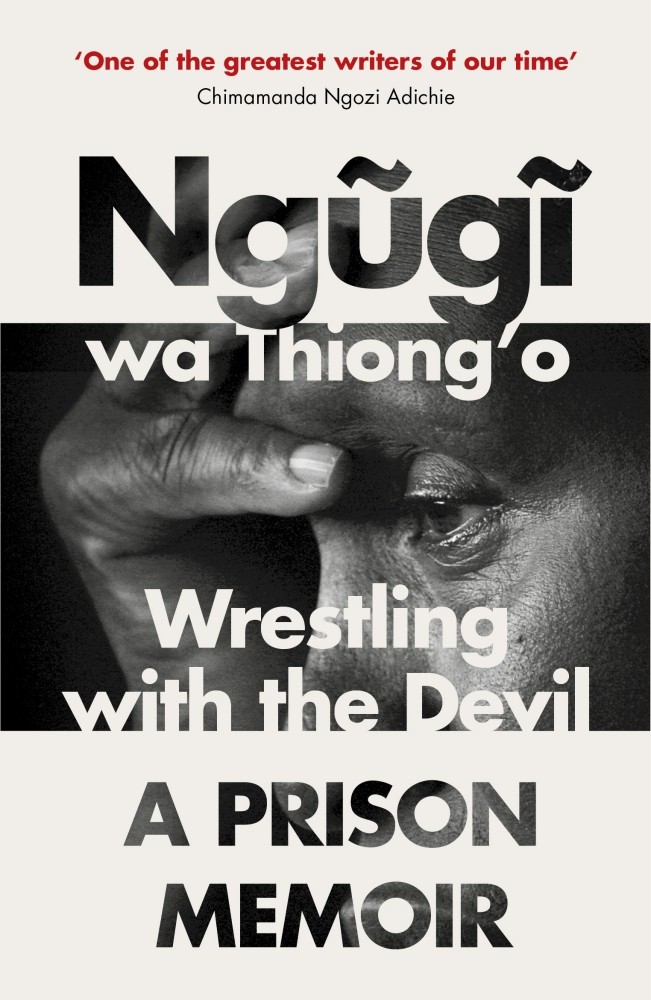

And now we have been gifted a reworked version of his powerful prison memoir Wrestling with the Devil covering his year – from December 1977 to December 1978 in Narobi’s maximum security jail. His crime had been to return to his native village with a play, critical of the government, which was to be staged by local people.

The same pen which landed him in prison proved his saviour once imprisoned – his classic novel Devil on the Cross was written covertly on toilet paper during his detention. This is both a worthy addition to the prison diary greats but it’s also a no-holds-barred review of British colonial misdeeds and a salute to the warriors of the Kenya Land and Freedom Movement.

It was an uneven battle: revolutionaries with rusty guns against the most powerful army on earth alongside its local militias. The casualty figures tell their own tale: during the eight years of the ‘Emergency’, 22 settlers were killed as against over 20,000 Kenyans branded ‘Mau Mau’ by the authorites. An additional 1,000 Kenyan prisoners were hanged, 400,000 held in concentration camps and more than a million rounded up in ‘enclosed villages’.

No wonder Ngugi rages in his prison memoir about the failure of the newly-independent state to acknowledge its debt to its heroes.

“I am not trying to write a story of heroism,” he says of his own detention. “I am only a scribbler of words. Pen and paper have so far been my only offensive and defensive weapons against those who would like to drown human speech in pool of fear — or blood.”

Appearing before a prison tribunal, set up by the government to counter criticism of its imprisonment of its political opponents, Ngugi must plead his innocence without knowing the charges against him; a charade he eventually refuses to grace with his presence. To receive medical treatment, he must assent to being chained. His insistence that the bullets of his jailors are faster than him cuts no ice and he chooses to forego medical treatment.

All these years later, and perhaps because prison is so integral a part of our own struggle sadness, Ngugi’s moving account of his ordeal still strikes a chord. The fear of death among the prisoners, their anguish at having no release date, their isolation from any source of news from the outside world and their dreams of freedom all loom large in this masterful work.

“For those who wait in prison, as for those who wait outside, dreams of freedom start at the very minute of arrest. Something might just happen; maybe somebody will intervene; and even when everything seems against any possibility of release, there’s the retreat to the final bravado, the plight can end only in either death or freedom, which I suppose are two different forms of release. So release of one sort or other is eventually assured.”

The recent case in the British High Court where hundreds of 40,000 elderly supporters of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army received compensation for torture they endured in British concentration camps revealed details of unspeakable atrocities. Indeed, the truth was even more grim, the cover-up more comprehensive, than the Andersonstown News editorials understood.

There is a bond that ties those who endured British rule — perhaps not fully realised because we mere Irish don’t have the opportunity to rub shoulders with our fellow-felons in the Commonwealth club — but Ngugi’s stirring prison diary reminds us that we will be forever tied to Kenya and its fearless fighters of sword and pen.

Wrestling with the Devil. A Prison Memoir: Ngugi wa Thiongo, Penguin Vintage, available from No Alibis Bookshop, Botanic Avenue.

A special talk, Countin-surgency from Kenya to Ireland will take place in St Mary’s University College on Friday 2 August at 3pm as part of Féile an Phobail.