In 1932, Michael McLaverty upended the tablets of stone on which the newly-born Northern state stood with his sparing but evocative novel Call My Brother Back; the first book to tell it as it really was for beleaguered Belfast nationalists.

Now, as we approach the shameful centenary of that grotty gerrymandered entity, a new book has come along which similarly shatters the smug consensus on which so much of our commentary about the still sidelined nationalist community is based.

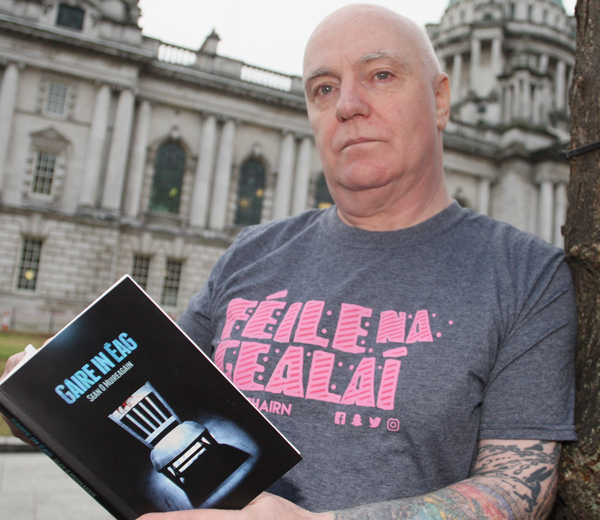

In ‘Gáire in Éag’ (literlly, ‘A Dying Laugh’) Ballymurphy writer — echoes of McLaverty’s own background there — Seán Ó Muireagáin has given us a master-craftsman’s collection of short stories based during the years of warfare in West Belfast. They are told with the reverence and respect you would expect from someone whose fictional characters populate the very streets and alleyways he himself walked and walks. These are stories sympathetically woven from yarns shared at wakes and barricades and they are told with all the authenticity and captivating power of a backstreet seanchaí.

And while the protagonists are sympathetically drawn — there are no psychopathic terrorist godfathers or feeble-minded IRA cannon-fodder here — there is deceit, treachery and even murder.

If your conception of Ballymurphy circa 1985 is based upon the ramblings of our mainstream media commentators scrambling for credibility or the pulp fiction ravings of Jack Higgins, then the short stories in ‘Gáire in Éag’ will be like epistles from another planet. If, however, you actually knew people who stored weapons for the IRA, sheltered republican active service units, engaged in armed struggle for the IRA or even betrayed the IRA — and most probably called them your neighbours — then these stories of ordinary people in extraordinary times is a tonic for the retired troops.

Of course, to enjoy this exceptional collection, you will have to be able to read Irish, the literary language of ‘John Boy’ Ó Muireagáin, even if not his mother tongue. That, the author says, is the book's strength — even if it means not all those who would be able to recognise themselves in its pages will get to enjoy it.

“I don’t think you would get a publisher for this book in English,” says Seán (in Irish). “To be published in English on the topic of our conflict, you need to have a certain point-of-view which often has not even the faintest connection to the reality we experienced. In ‘Idir Dhá Thine Bealtaine’, I tell the story of a woman who kept an arms dump for the IRA. I don’t judge her but I do tell her story as a writer who is very proud of the republican and nationalist people from whom I come. After all, the people who hid IRA weapons were, some might say, more heroic than the people who did the shooting. Every night, they went to sleep dreading the early-morning raid. And yet, no-one is telling the story of those overlooked heroes who are at the core of any revolution?”

A member of the extended Ó Muireagáin tribe which spearheaded the Irish language revival in the Upper Springfield area, Seán, now 57, didn’t start writing until he was well into his forties.

“I started with poems about ten years ago,” he says. “They helped me make sense of my own life but about four years ago I started to try my hand at short stories. I wanted to tell the story of my own community, a story which hasn’t been told despite the mountains of books which have been written about us. I felt I could do that in Irish easier than in English. The Irish language community is tighter and more understanding than the larger English language public and you can sidestep the inevitable condemnation which would rain down on anyone who wrote stories with this worldview in English.”

His fluent story-telling style is comfortable and engaging and firmly rooted in lives which would be considered humdrum and ordinary if there wasn’t a war raging in the background. His fealty to his subjects is reminiscent of the master Basque writer Bernardo Atxaga who tells the story of an entire people without leaving the tiny mountain village of Obaba. But the Ballymurphy man’s genius with words doesn’t stop there for in setting his stories against the background of the battlefield, he takes up the mantle of Kenya’s greatest author Ngugi wa Thiong’o whose books demolish the previously accepted white-man’s-burden version of the Mau Mau (Land and Freedom Movement) struggle against British colonialism.

However, anyone expecting The Victor comicbook-style war stories of republican derring-do is likely to be disappointed.

“The stories are about war and conflict at a very personal level; how conflict affected the lives of ordinary people,” says Seán. “In ‘Sceithire' (‘Informer’), I look at the informer not in traditional black and white republican terms but with empathy for the tout's family and, of course, with an eye to the mirrors-within-mirrors nether world of informers.”

The longest story in the collection, Pól, is a dark, macabre helter-skelter in which an enraged lover sets out on a murderous rampage, covering up his deeds in the undergrowth of Troubles’ killings. “I always wondered if someone with malign intent could literally have got away with murder and through Pól I get to let my imagination roam free,” says Seán. “However, no-one should reopen any cold cases; all my characters are fictional. True, many are inspired by a titbit of true information or by a real event but ultimately, this is fiction not loose talk.”

Seán is keen to let his short stories do the talking for him but he does have a fascinating story of his own to tell — perhaps in memoir form now that he is taking early retirement from the Irish language agency Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta to focus on his writing. A poet, short story writer (another work of his won a special award at the Oireachtas in November past), a consummate sean-nós singer and even a stand-up comedian, Seán was a renaissance man before the term was invented but his renaissance started with the Irish language.

“I am just an ordinary person who had the good luck to discover this Irish language which has nurtured me since I was a teenager,” he says. “Now I want to give back by writing plays, poems and stories which do justice to the ordinary people who make up my community and who have come through the most extraordinary times with their heads held high.”

Seán Ó Muireagáin has no plans for an English language translation but what brought Atxaga and Ngugi to a wider audience, the gift of translation, could reveal this gem of a book to a wider audience in the time ahead. Indeed, that would be the perfect way to mark the centenary of our own wee country in 1921! A Dying Laugh indeed.

‘Gáire in Éag’ (published by Éabhlóid) will be launched in An Ceathrú Póilí bookshop in An Chultúrlann at 2pm on Saturday 2 February.